Over the course of my life, I have been convicted in four separate trials, sentenced to a total of 69 years in prison, and after many appeals served just over 20 of them – the first two in maximum security. I was finally released on parole in 1997.

Given the length of time I was incarcerated, you might be thinking that I was involved in hard drugs or violence. After all, some murderers do less time than I did.

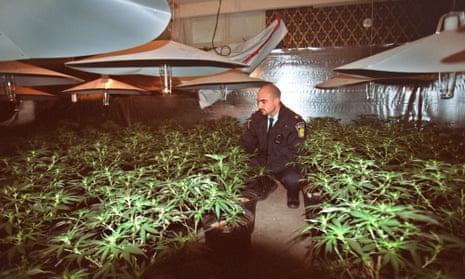

But my crime? Conspiracy to import, possess and sell cannabis.

I brought in tons of hash from the Middle East and tons of pot from Jamaica, Mexico and Colombia. Toronto’s infamous Rochdale College was my home base. After my first trial, I told the judge: “I’m going to do it again” – and I did – but I can assure you I never got involved with any harder drugs, let alone anything violent. I was strictly a pot guy: a hippy capitalist from Belleville, Ontario, who wanted as big a piece of the North American market as he could get.

In jail, I saw myself as a prisoner of the war on drugs – one of the thousands of others who lost part of their future in the long, cruel and ultimately futile attempt to stop people from buying, selling and smoking weed.

Norman Mailer testified on my behalf at my first trial, Neil Young at my second. Young told the court that he took exception to the prevailing stereotype of deadbeat pot smokers who could never make a positive contribution to society, pointing out that he was a prodigious toker and yet he still likely paid more taxes than everyone else in the court room combined.

Now a new day is dawning in Canada – or so it seems. Possession of pot for recreational use is about to be legalized. Canadians will be able to possess up to 30 grams, buy it, share it, put it into edibles and grow a few plants.

To be honest, I’ve never considered myself to be a marijuana activist. I wasn’t a campaigner for legalization: I was making big money, and legalization would have been bad for my business.

I also don’t trust or respect politicians, especially when it comes to pot. In 1969, the prime minister, Pierre Trudeau, set up the LeDain Commission to study the pot scene in Canada. After hearing from thousands of Canadians, the report recommended cannabis possession be legalized. I was 18 at the time, a pot smoker and hopeful. Nothing happened.

Fifty years later, however, the war on pot is finally over, and my side has won. So why am I not celebrating?

Let’s start with the movement to grant amnesty to people with past cannabis convictions. I’m glad that the prime minister, Justin Trudeau, has said he plans to “move forward in a thoughtful way on fixing past wrongs that happened because of this erroneous law”.

If the law is so “erroneous”, however, why is his government continuing to bust people for possession? In 2016, more than 17,000 Canadians were charged with a law that will soon disappear. Offering them amnesty would be a nice gesture, but the damage will have already been done. Why charge them in the first place?

And how would amnesty work? After legalization in their states, several US cities, including San Francisco, Seattle and San Diego, moved to expunge all records of felony convictions for cannabis possession. Will Canada do the same? If not, amnesty will be a hollow gesture. Even then, Canadians with pot convictions may still not be allowed to travel to the US because American authorities have their conviction records on file.

I’m also bothered by the fact that the government’s current plan is to bar people with pot convictions from participating in the huge marijuana economy that is now emerging. We have the expertise. We know how to grow high-quality plants. We have the distribution networks. The government’s policy is unfair, punitive and discriminatory: if it really believed in amnesty, it would let people with non-violent records for possession lead the way.

Instead, the government has turned the pot economy over to the people who lost the drug war: the cops and politicians who were responsible for destroying so many lives by turning pot smokers into criminals. They’ve been given the keys to the vault. They’ll be profiting from the same activities they used to prosecute. The hypocrisy is staggering.

Look at Julian Fantino, the former chief of the Toronto police service. In 2015, then a Conservative MP, Fantino declared his complete opposition to legalization, likening the decriminalization of marijuana to legalizing murder.

Today, he’s on the board of directors of Aleafia, a company that connects patients to medical marijuana. When asked about his change of heart on pot, Fantino replied that he had embarked on a “fact-finding mission” and discovered that marijuana was not the demon drug he once thought it was. Perhaps he should have done some fact-finding before he started tossing people in jail.

Also on the Aleafia board is Gary Goodyear, who held several cabinet positions in Stephen Harper’s government – the same government that proposed mandatory minimum sentences for anyone convicted of growing at least six marijuana plants. So is Raf Souccar, a former deputy commissioner of the RCMP whose portfolio included drug and organized crime enforcement. Former deputy Toronto police chief Kim Derry and ex-Ontario premier Ernie Eves are also members of the old law-and-order crowd who have rushed to cash in on the legalization of marijuana.

On its website, Aleafia describes Fantino as a “leading expert on drug enforcement”. They’ve got that right. I’ve never had the pleasure of meeting the man, but shortly after joining the Toronto police department in 1969 he became a member of the drug squad, one of the hundreds of Toronto cops who pursued me relentlessly throughout the 1970s. Now he gets to cash in on the legalization of marijuana, while people with criminal records for something that is soon to become legal languish on the sidelines – or, in many cases, still in jail. If I’m a criminal, what word would you use to describe Fantino and all the other ex-cops and politicians who are now looking to get rich by switching to the other side?

A simple amnesty is not enough. It should include an apology for ruining the lives of hundreds of thousands of people for no legitimate reason. They should be asking us to forgive them. I sentence them to have to live with themselves for the rest of their lives.

- Rosie Rowbotham is a former producer at CBC Radio